'Public buildings are the most splendid monuments of a great and opulent people'

— Robert Adam.

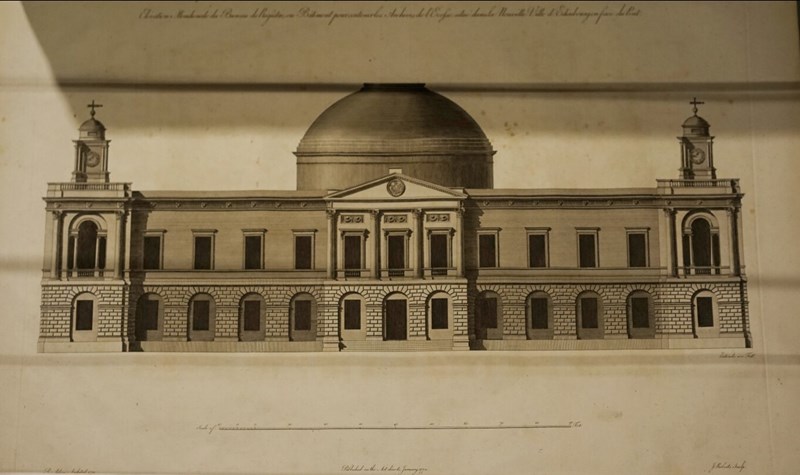

Register House, Edinburgh.

View zoomable image

Scottish roots

Robert Adam and his brother James were products of the Scottish Enlightenment. In Robert's case, the Enlightenment characteristics of logic, common sense, independence, curiosity and pragmatism were also mixed with a strong visual sensibility.

During his time at university, Robert had ambitions to become a painter and so probably attended one of the local Edinburgh drawing schools. This was balanced by the influence of his father's extensive library back in the family home in Fife. Here along with the classical texts and histories, there was a collection of illustrated architectural books in English, French and Italian.

Probably the most visually stimulating item in the library was a small collection of Dutch prints and landscapes. These encouraged Robert in his more sophisticated experiments in composition and perspective. Many of his drawings are now kept in Sir John Soane's Museum in London.

Fort George

When his father William died in 1748, Robert went into partnership with his elder brother, John. They undertook the building and re-building of the Highland forts after the 1745 Jacobite Rising.

As Royal Master Masons, they were the contractors for building Fort George, just outside Inverness. As a military fort, it was the culmination of a military tradition which offered Robert a visual overview of the history of forms and functionalism.

1749 plan of the new Fort George attributed to

William Skinner, engineer.

View zoomable image

Public architecture

Glasgow Trades Hall

Robert felt that public commissions were a judgement of an architect's career and his lack of success in this area was a big disappointment for him. He had been appointed as joint architect of the King's Works in 1761, which should have led to big commissions in England but he was effectively excluded from high-profile commissions at the Royal palaces.

To fill the gap, Robert instead focused on speculative building and in expanding his Scottish practice.

Buildings in Scotland

Old College, University of Edinburgh

© Kim Traynor

After the 1780s, Robert did not build many significant buildings in England beyond London. His energy was now mainly directed towards work in Scotland, where he enjoyed a successful country-house practice and had several public commissions in Glasgow and Edinburgh.

His visual imagination was also now drawn back to his Scottish roots. The conceptual grandeur of the Adelphi scheme was repeated in his urban developments in Glasgow and Edinburgh.

Robert's account book for the year 1791-2 shows the energy he had in directing buildings. He worked across almost the breadth of Scotland while his base remained in London. It was virtually a one-man operation as his brother James did not have much to do with the practice at that time.

Robert's work on the Register House in Edinburgh of 1774 and later at the University of Edinburgh (1789), Bridewell prison (1791), the South Bridges scheme (1790) and in Glasgow on the Infirmary and University (1790s) all came towards the end of his career. They were finished by his brother James after 1792.

Scottish connections

Throughout his life, as well as public commissions Robert also relied on his Scottish connections, and he remained loyal to them. One of the grandest houses he was commissioned to build was Luton Hoo (1766), for the third Earl of Bute. Although it was never fully completed, Bute commissioned other work and had ensured Robert was appointed as Royal Architect in 1761 along with Sir William Chambers.

At a time when Bute was a deeply unpopular Prime Minister, Robert bravely publicised his gratitude for the Earl's protection and friendship in 'The works'.