2023 marks the centenary of Scottish writer Dorothy Dunnett (OBE), best known as a writer of historical fiction. To celebrate, members of the Dorothy Dunnett Society have reflected on items in the archive.

By Carole Richardson

A sequence of letters exchanged during the development and writing of 'The Ringed Castle', (Book Five of the 'Lymond Chronicles', partially set in Russia in the 1550s) tells the story of a serendipitous discovery and how it evolved into a substantial feature of the novel. It also throws light on both Dorothy Dunnett's meticulous research and her thoughtfulness towards those who helped her along the way.

'The Song of Baida', a Ukrainian folk ballad glorifying the exploits of Dmitri Vishnevetsky, the real-life, and larger-than-life, Lithuanian Prince and charismatic leader of Cossacks, so joyously and raucously sung by his loyal followers out on campaign, is so impactful within the narrative of 'The Ringed Castle', that it's hard to imagine his character without it. Yet it's entirely possible that including it in the novel was not a part of Dorothy Dunnett's original plan, as her discovery of it may only have been due to a lucky combination of circumstances. Making the most of unexpected gifts like these was part of the way she operated as a writer, as many other documents in this archive bear witness.

Dorothy Dunnett thoroughly enjoyed her foreign research trips and often took her family along. During the summer of 1970 (which was of course still during the Soviet era), she visited Russia as part of her research for 'The Ringed Castle', accompanied by her husband and one of her sons. Her aim was to see as many as she could of her proposed locations in Moscow and its environs, and to meet up with helpful Russians with whom she had been put in contact.

One of those contacts was Professor Aleksandre of Moscow State University. Dorothy Dunnett and her family spent a memorable evening at his home in Moscow, in the course of which the Professor lent her a book of Ukrainian folk ballads (see Letters 1 and 4). Several of these concerned Dmitri Vishnevetsky and his band of Cossacks, who inhabited the wild lands beyond the then borders of Russia, south of the River Dnipro. We cannot know whether she knew beforehand that she would come away with this material, whether she even knew it existed, or whether it was a truly unexpected, but very fortuitous, discovery for her.

Letter 1: Dorothy Dunnett to Professor Dennis Ward, 26th October 1970, Acc.12135/894. Copyright the Estate of Dorothy Dunnett.

At any rate, on her return, Dorothy Dunnett immediately set about getting the ballads translated, to which end, in October 1970, she sought the help of Professor Ward at the Russian department of Edinburgh University (Letter 1). At this point all she asks for is "a fairly rough translation", which suggests that initially she was just looking for information to flesh out her characterisation of the Cossack leader, with no idea of using the ballad itself in the novel.

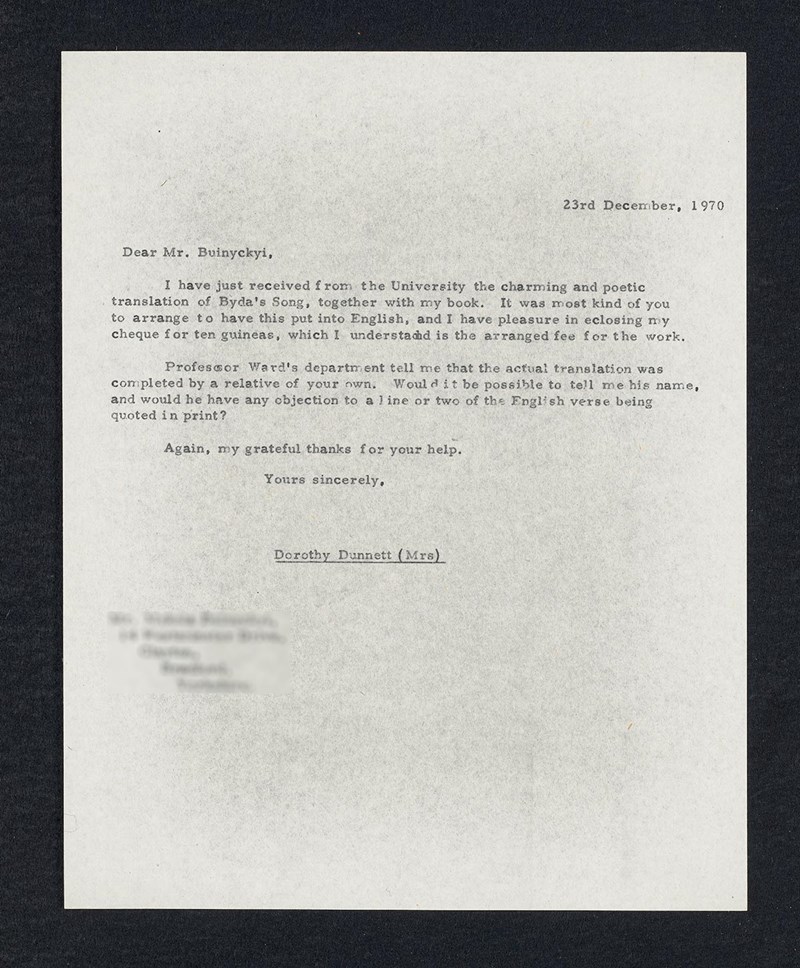

The archive does not have the whole sequence of correspondence, so we do not have Professor Ward's reply. However, Letter 2 suggests that the Professor then went ahead and arranged matters through his own contacts. The translation was duly carried out and returned to Dorothy Dunnett via the university. Letter 2, dated 23rd December 1970 (the author clearly did not let Christmas interrupt her work!), is addressed directly to the next person in the chain, Mykola Buinyckyi, a (presumably Ukrainian) gentleman living in Yorkshire. It included a cheque in payment for the translation work (ten guineas was the going rate at the time apparently) to be passed on to the actual translator, who is revealed elsewhere to be an old schoolfriend of Mr Buinyckyi's, not a relative as Dorothy Dunnett states here.

Letter 2: Dorothy Dunnett to Mykola Buinyckyi, 23rd December 1970, Acc.12135/894. Copyright the Estate of Dorothy Dunnett.

She thanks him very politely for the "charming and poetic translation of Byda's (sic) song", but she still does not appear to be considering using more than a small fraction of the poem, as she only asks permission to include "a line or two of the English verse" in the novel.

The same day she wrote again to Professor Ward (Letter 3), thanking him for his help, and expressing her evident satisfaction with the translations, which she describes as having been "most efficiently and poetically done".

Letter 3: Dorothy Dunnett to Professor Dennis Ward, 23rd December 1970, Acc.12135/894. Copyright the Estate of Dorothy Dunnett.

These two letters in themselves are unremarkable, just the author going through the necessary business side of her work. But they serve as a reminder of the many little jobs that needed to be done. It wasn’t all about the research and the writing. And they are still part of the story, each one progressing it a little further.

In early January 1971, Dorothy Dunnett received a hand-written letter from Mykola Buinyckyi, thanking her for her payment, and elaborating most helpfully on the translation carried out by his old schoolfriend, Yaroslav Baran (who receives a credit in the front matter of the book). In the letter, Mr Buinyckyi explains that he and his friend had several meetings to discuss the translation work and how best to undertake it. In the end they decided that the precise, thoughtful, rather academic prose of a professional translation was not what was required here. They plumped instead for a freer, more poetic rendering, which would better capture the atmosphere of the ballad: more redolent, you might say, of the wild steppe.

He adds that his friend was delighted to be given the work, and as a result had decided to read more Ukrainian poems! He also gives permission for Dorothy Dunnett to quote from the English translation.

Without access to the original ballad (and indeed a knowledge of Ukrainian), it's hard to know how closely the version of 'The Song of Baida' used in 'The Ringed Castle' follows it, and how much is the work of the translator. But Dorothy Dunnett obviously loved it. Her original request for a "fairly rough translation" elicited such an evocative and beautiful rendition that in the end she couldn’t resist using substantial chunks of it, threading the verses through the narrative so that the ballad became a central feature of the southern campaign episode. It may even have helped her shape the character of Prince Vishnevetsky as she portrayed him in the novel.

The final letter in the sequence, Letter 4, was written six months later, in June 1971, once more to Professor Aleksandre in Moscow. 'The Ringed Castle' is finished, she knows how she has used the material he provided for her, so she is now in a position to write and thank him properly for it. But, typically for Dorothy Dunnett, this is not just an exercise in tying up loose ends. Not only does she take the trouble to thank the Professor once again for his hospitality during their visit – a very genuine and heartfelt expression of thanks – but she also includes gifts for him and his wife which she has clearly given a lot of thought to choosing. And there is also the promise of a copy of the novel itself, once it is published.

Letter 4: Dorothy Dunnett to Professor Aleksandre, 11th June 1971, Acc.12135/894. Copyright the Estate of Dorothy Dunnett.

Altogether, this sequence of letters tells in microcosm much about Dorothy Dunnett's approach to her work. The thoroughness of her research was legendary. Along with the huge amount of background material she read, she visited as many of her locations as she possibly could, to do on-the-ground research. She met and talked with people who could give her, first-hand, the benefit of their knowledge and expertise. She went straight to the top when she needed outside help, here writing directly to the head of the Russian department at Edinburgh University (albeit on the recommendation of friends). And she always sought the most professional assistance she could, to ensure that her own information was as accurate as possible.

But alongside that, she never forgot the human side of being a novelist. She was always kind, thoughtful and generous towards anyone she encountered, be they fans of her work, aspiring novelists themselves, or, as here, people who had helped her with her own research. In the story told by these letters of how 'The Song of Baida' came to feature in 'The Ringed Castle', readers of her work can learn so much about both Dorothy Dunnett the historical novelist and Dorothy Dunnett the human being.

"In the market place of the Khanate

Baida drinks his mead

And Baida drinks not a night or an hour

Not a day or two …"

(from 'The Song of Baida', translated by Yaroslav Baran, 'The Ringed Castle', Part Two, Chapter 12)

Acc. 12135/894