2023 marks the centenary of Scottish writer Dorothy Dunnett (OBE), best known as a writer of historical fiction. To celebrate, members of the Dorothy Dunnett Society have reflected on items in the archive.

By Heather Jacobson

While working on 'The Lymond Chronicles', Dorothy Dunnett began interspersing her historical fiction with detective novels featuring the unglamourous but internationally renowned portrait painter and secret agent Johnson Johnson. A key (nonhuman) character in the novels is Johnson's yacht Dolly, the name of which was included in the book titles (for example, 'Dolly and the Doctor Bird') until the decision was made to change them. These books allowed Dunnett to use her extensive personal knowledge of portrait painting and yachting in ways not possible for her historical fiction.

The 'Johnson Johnson' (or Dolly) books are mad-cap thrillers in which Dunnett was free from the strictures of historical record to have fun with the things she loved to do in her writing: lay out an intricate puzzle for readers to solve, set her plots in far-flung and interesting locations, and create unforgettable (and unreliable), sharp-witted and observant characters. She regularly placed them in implausible, zany but dangerous situations (a hurricane is a more mundane danger, while a chase scene involving street sledges in Funchal, Madeira, is less so).

Although writing the Dolly books served as an escape for Dunnett, by no means did she relax her rule of constructing a plot on a foundation of solid research. She visited every location set within the books and took detailed notes not only of what the place looked, sounded and smelled like but also of local slang, snippets of overheard conversation and advertisements. And she never wasted any experience. For example, she was fond of telling the story of a research trip to the Bahamas for 'Operation Nassau', on which she took her mother. The actress Brigitte Bardot happened to be on the resort island Dunnett had come to research, and she (Bardot) captivated the whole population with some nude sunbathing. Dunnett kept her respectable English mother on the golf course for hours to avoid the spectacle, and as a result that is where the body is found in the novel she came to write.

What is more, each Dolly book is told from the point of view of a young professional woman, each of whom is an expert in her field. This meant that Dunnett herself became an expert in professions ranging from medicine and makeup artistry to catering and astronomy in order to develop her narrator’s character and voice.

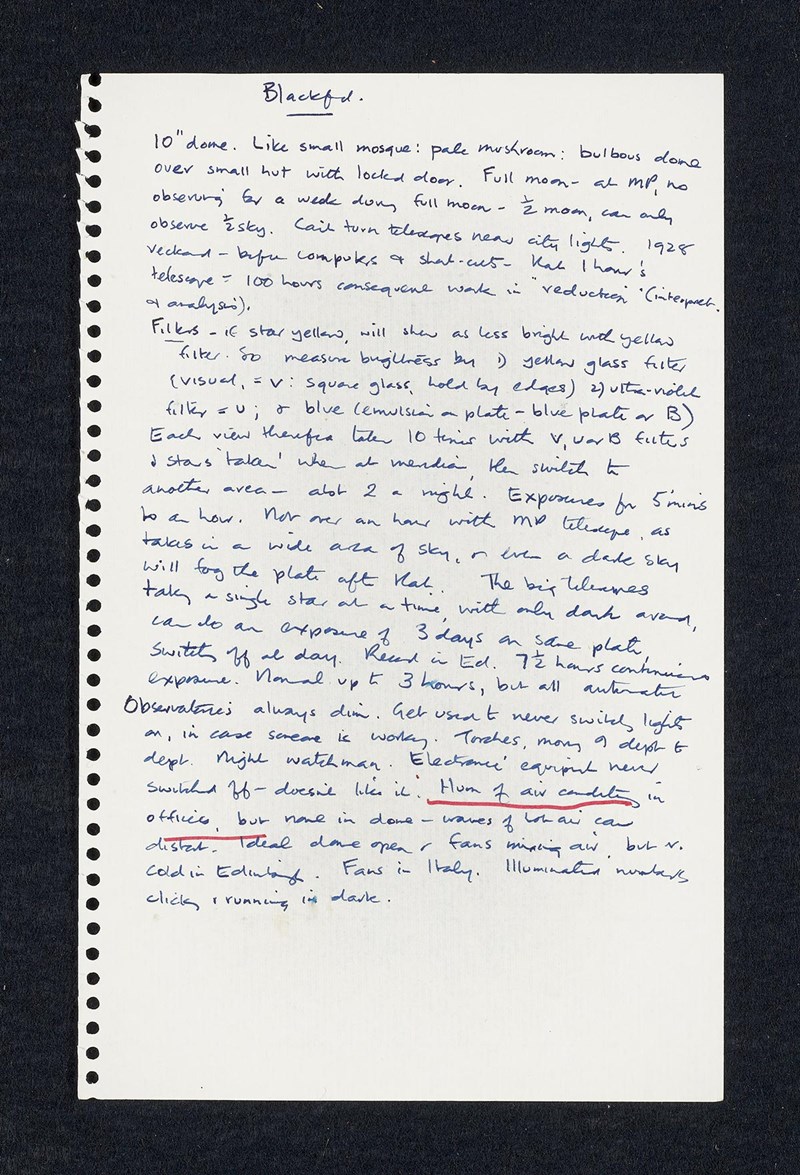

Astronomer Ruth Russell is narrator of 'Roman Nights' (first published as 'Dolly and the Starry Bird' in 1973), and many scenes take place in the observatory where she works, including the discovery of a body in a refrigerator. In the National Library of Scotland archive of Dunnett’s papers can be found notes that she made from astronomy articles published in 'Nature' magazine to get the terminology down, as well as of a research visit to an observatory. Dunnett did not have to travel to Rome, the location of Ruth's observatory, for this research (though she did go to Rome). She had an observatory in her hometown of Edinburgh. Looking at the notes she took on this visit to the Royal Observatory on Blackford Hill, she not only set down on paper a physical description of what it was like but also notes about an astronomer's typical working routine and how they moved about the space (don’t switch on the lights!).

Research notes from visit to telescope on Blackford Hill, Edinburgh, Acc.12135/435. Copyright the Estate of Dorothy Dunnett.

What shines out of the Dolly novels is Dunnett's wit and sense of humour. These shimmer through all of her novels, of course, but they seem especially light and fresh in the Dolly books because Dunnett applies them to contemporary characters, events and social trends. For example, Ruth’s lover in 'Roman Nights' is famous fashion photographer Charles Digham, who (not surprising for a Dunnett character) has an interesting sideline: he authors obituary verses. Ruth peppers her narration of the novel with Digham's witty remembrances of the dead (perhaps she helped him compose some).

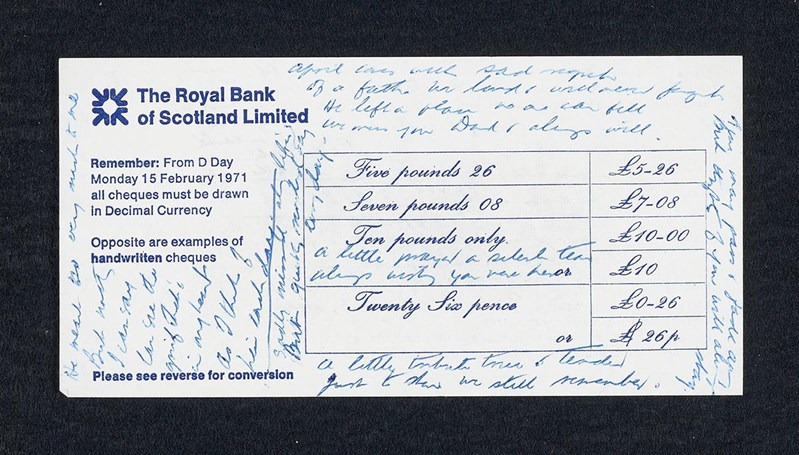

The Dunnett archive contains a few pages of obituary verses written out by hand. Shown here are some scrawled on a page from a chequebook. Clearly Dunnett used whatever paper was convenient. Some of the verses here read like remembrance poems that can be found on funeral services websites and in sympathy cards today, so perhaps Dunnett found these in a brochure or such like and wrote them down for inspiration.

Chequebook page annotated with obituary verses, Acc.12135/437. Copyright the Estate of Dorothy Dunnett.

By and large, Charles Digham's verses are more … unusual and rather specific.

Sweet Mem'ry's Chord

Was Touched Today

They Came and Took

Your Teeth Away

Your Wig had Gone

Your Gas Limb Too

The Plastic Joints

That Rivet You

Your Contact Lenses They Removed

And All About You that We Looved.

('Roman Nights', Chapter 6)

We will not build a cross for you

With angels all a-simper

Because, my friend, you left us with

A bang and not a whimper.

('Roman Nights', Chapter 1)

Acc. 12135/435–437